Fire Escape! Malmo Collaborative AI Challenge

Video Summary

Project Summary:

Our project aims to train an agent to complete a set of challenge maps in the smallest number of steps while maximizing remaining health. The challenge maps will consist of obstacles such as fire blocks, holes, and elevated blocks which the agent must learn to navigate and avoid obstacles when necessary.

Our highest priority is finding the minimal number of steps possible to complete a map without dying. Our second priority is taking the least amount of damage while completing the map. The input for our agent will consist of the types of block and elevation of blocks on the map. The output will be the chosen movement of the agent. Our agent can walk, run, jump onto a block, or jump over a block in any of the four cardinal directions. We aim for the agent to learn the shortest route possible, while taking the least amount of damage during the challenge run using Q-learning and Deep Q-learning.

The motivation of our project is to implement an algorithm that can be generalized to be able to learn the shortest path while minimizing damage taken for any given map. In particular, this would be especially useful in game speed-running communities to find the lower bounds for map completion time. This problem cannot be solved with algorithms such as Dijkstra’s because it would require an exponential amount of code to consider every variable and obstacles on the map. For our project, we have 16 different actions, four different obstacles, and multiple health states which lets our agent decide on actions with more flexibility. It would be difficult for Dijkstra’s to achieve the same level of flexibility as Deep Q-Learning.

Approaches

Since our project involves having an agent learn the shortest path from a start block to a goal block, the obvious baseline for our project would be Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm. Our algorithm should be able to find a path the same length as Dijkstra’s while minimizing the amount of damage taken. To do this we decided that Reinforcement Learning was the best approach.

1. Algorithm

1-1. Initial Approach

Figure 1: Q-learning Update Function

In the first version of our project, we used the Q-Learning update function shown in Figure 1 to teach our agent to navigate the map safely. Q-Learning is an algorithm that teaches an agent which action to take given a state through rewards and punishments. For our implementation of Q-learning, we define each unique block on the map to be a state. Q-Learning uses a table of Q-values which is used to rate an action based on a given state and the value of the next best action. The learning rate will determine the degree of change to the Q-table per iteration. The discount factor determines how much future actions will impact the rating of the current action.

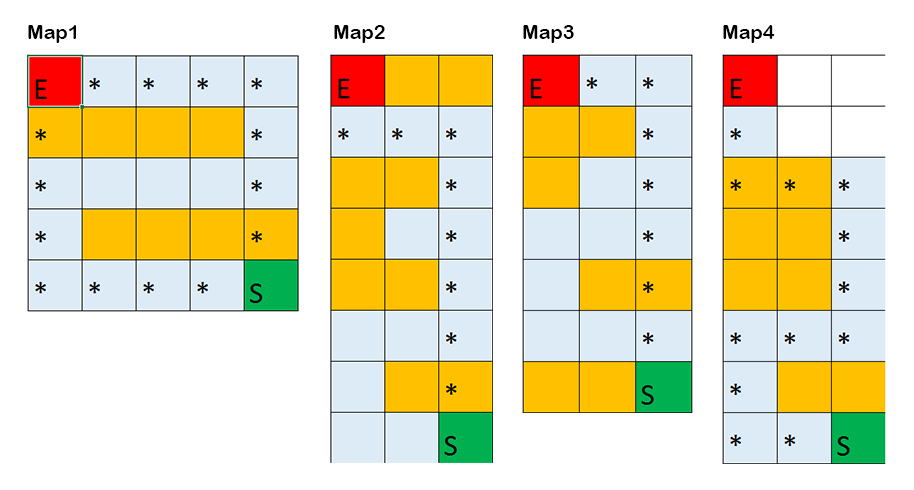

Figure 2: Initial set of maps

For the first version of our algorithm, we kept the size of the map to be less than 25 blocks with 3 health states: full health, less than ⅔ health, less than ⅓ health. For our action states, we allow the agent to have four different actions: forward, backward, left, and right. This would produce a Q-table with the size:

(number of blocks on map * number of health states * number of action states) = 25*3*4 = 300

For each action the agent completes, a positive reward or negative reward will be given based on the resulting state the agent is in. The reward function we implemented uses three main factors to calculate the reward given for an action:

1. Distance from goal block calculated using Dijkstra’s Shortest Path

2. Amount of health remaining

3. The agent’s survival after an action

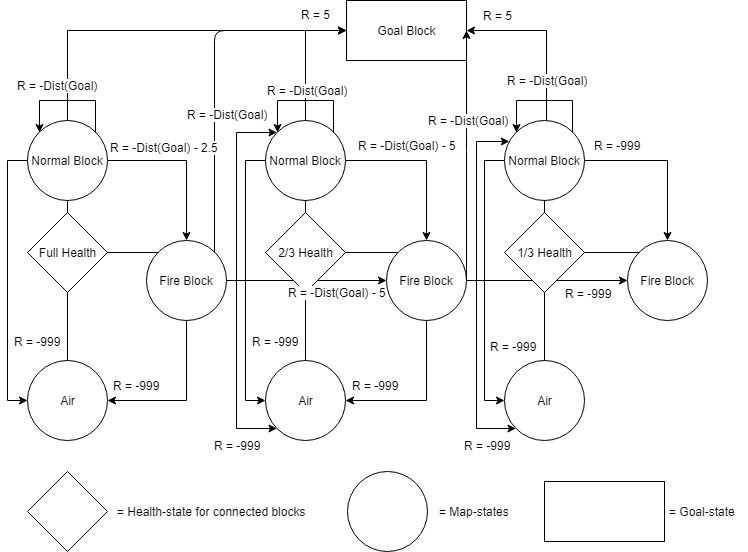

The main heuristic we used to determine the reward given to an agent is the distance from the goal block. The farther away from the goal block, the lower the reward given. This will incentivize the agent to get closer to the goal block with each action. A reward will also be given when the agent reaches the goal. During the agent’s adventure learning the map, if the agent happens to die from falling or fire, a large negative reward will be given to deter the agent from committing the same action in the future. The negative reward given when stepping on fire will be calculated based on the health state the agent is in. When the agent is max health, a small negative reward is given for stepping on fire. This is to encourage the agent to go through fire if it can shorten the distance from the goal significantly. As the agent’s health decreases, the negative reward will increase to deter the agent from dying to fire damage. A diagram of the Markov Decision Process is shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3: Markov Decision Process

Note:

1. Normal Block includes elevated blocks.

2. If the agent stays in the same block (ex. the agent uses move 2 to the elevated block), -20 reward is given to deter the agent from committing the same action in the future.

1-2. Improved version

While tabular Q-learning algorithm performs adequately for a Q-table of size 300, we wanted to expand our maps to have a maximum map size of 100 blocks, which translates to a state-space of 100.

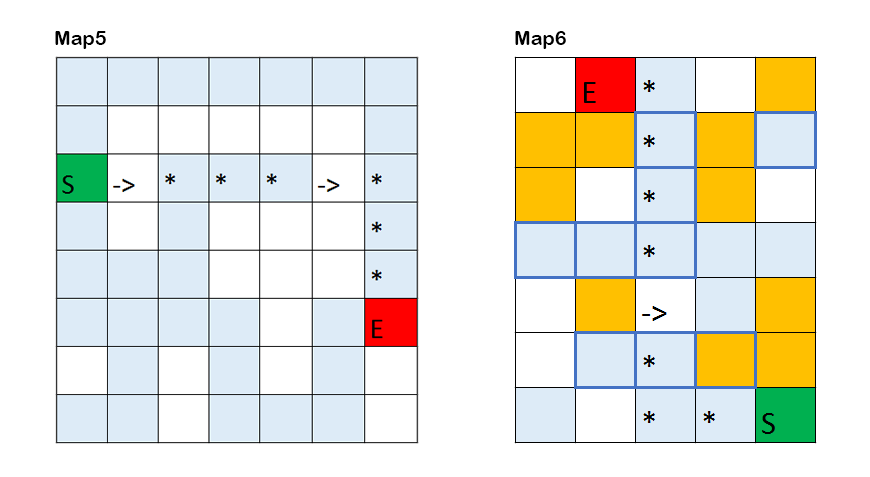

Figure 4: Newly added maps

With the map size expansion, we also added 2 new obstacles into the maps. The maps now include raised blocks and gaps which the agent would need to learn to navigate and find the shortest path. With the inclusion of new obstacles, we also added 12 new actions to the action-space making a total of 16 actions available to our agent. The actions available are:

Improved Action State

['movenorth 1', 'movesouth 1', 'movewest 1', 'moveeast 1',

'movenorth 2', 'movesouth 2', 'movewest 2', 'moveeast 2',

‘jumpnorth 1’, ‘jumpsouth 1’, ’jumpwest 1’, ‘jumpeast 1’,

‘jumpnorth 2’, ‘jumpsouth 2’, ‘jumpwest 2’, 'jumpeast 2']

move 1 : the agent can move one block

move 2 : the agent can move two blocks in the same direction

jump 1 : the agent can jump up one block

jump 2 : the agent can jump over one block

With the new additions to the state-action space, the final version of our project would have a max Q-table size of:

(# of blocks on map * number of health states * number of action states) = (100 * 3 * 16) = 4800

This is significantly larger than our initial state-action space which causes the tabular Q-learning algorithm to require far more sample and time to converge on an answer. As an attempt to improve the performance of our agent, we decided to implement a one-layer Deep Q-network.

1-3. Advantages and Disadvantages

As the size of the Q-table increases, tabular Q-learning becomes more inefficient as it requires much more samples to sufficiently explore and update enough of the state-action space to converge to an answer. This usually results in a local maximum rather than a global maximum without over running it on a large number of samples. Furthermore, it also requires a large amount of memory to store a table of size 4800. In contrast, Q-networks uses a different method of updating Q-values in the table. Our Q-networks uses the sum-of-square loss function which calculates the squared difference between the predicted Q-value and the target Q-value.

Figure 5: Loss Function

Q-networks uses the loss function and backpropagation to propagate the gradient of the loss through the network. This allows each action to affect more than one state’s Q-value at a time, effectively speeding up the algorithm. This is particularly noticeable for larger state spaces. The ability to add layers and activation functions allows for much more flexibility for future expansion, such as adding new obstacles and moving enemies.

While Q-networks offer better coverage for large state-action spaces through backpropagation, they do so at the cost of stability compared to tabular Q-learning. Because backpropagation causes each action to affect multiple states, this means that fine tuning reward values is very important. Each reward value and parameters are more impactful to the result of the training now. In addition to that, neural networks also take a lot of time and computational power to train, especially if the hyperparameters and other values are not tuned optimally. Lastly, training neural networks on a mid-tier graphic card is slow and time consuming.

2. Implementation

2-1. Q-network Algorithm

Our implementation of Q-network Algorithm is shown in the pseudo-code below:

Figure 6: Q-Network Algorithm

With all the changes to the Q-learning algorithm, we updated our main heuristic function, Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm. The new heuristic function needs to take into account the ability to jump over air blocks. In our initial implementation of Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm, we only considered solid blocks that are directly connected to each other as walkable. With the implementation of jump, this is no longer the case. The agent can now jump over a single air block to reach a block directly across from it. To solve this problem, we implemented a constrained version of Dijkstra’s which connects solid blocks with a single air block in between them. This allows our previous implementation to continue working correctly.

Evaluation

Our evaluation method is separated into two parts: the quantitative measures and qualitative measures. For our quantitative measures, we kept track of several key variables during runs to determine that the agent is functioning as intended and accomplishing its goal. For our qualitative measures, we focus on gauging whether the agent can find the shortest path. If there are multiple shortest paths, the agent should choose the path that maximizes health.

Quantitative Measures:

The quantitative evaluation of our algorithm is based on these three metrics:

1. Reward values per episode

2. Number of moves per episode

3. Number of successful episodes

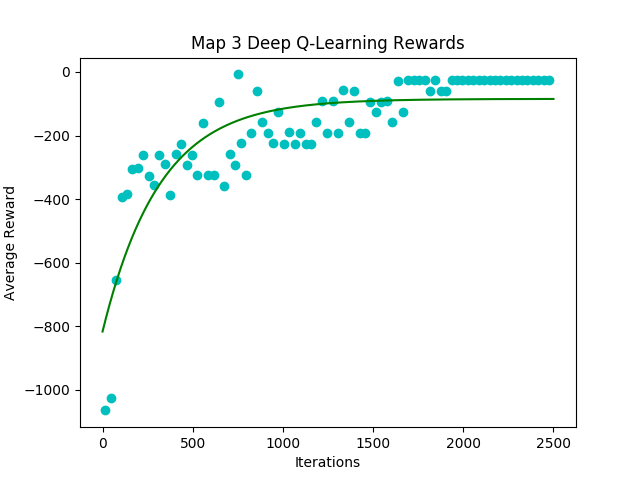

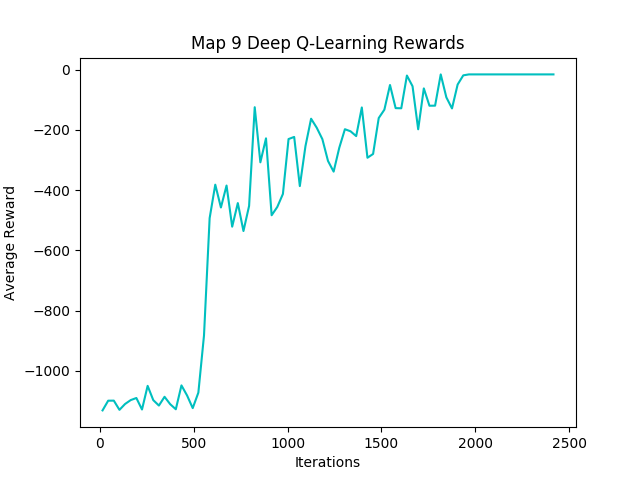

These three metrics help us measure the agent’s performance by measuring if it is continuously learning and improving the path it knows. The main metric we use to determine if the agent is learning is the reward value per episode. By keeping track of this metric, we can gauge if the agent is improving on the action it chooses at each state. The reward value per episode indicates the quality of the path chosen in that episode. An episode where the agent dies or makes several inefficient actions will result in a low reward value at the end of the episode. An episode where the agent optimizes its action and chooses the optimal path will result in the highest reward value. Our main goal is to have the agent continuously achieve the maximum reward value per episode at the end of a training session. Figure 7 and Figure 8 below shows the reward value per episode in one training session.

Figure 7: Map3 Reward Per Episode

As it can be seen in Figure 7, at the beginning of the training session, there is a large variance in the reward value per episode. As the agent progresses through the session, the variance decreases and the reward values converges to the highest reward value. This shows that our agent has learnt the optimal path for the map. The same trend applies to Figure 8 and the our other maps.

Figure 8: Map9 Reward Per Episode

The metric “number of moves per episode” and “number of successful episodes” lets us gauge if the agent is successfully learning to avoid lethal obstacles. As the number of episodes increases, the number of both metrics should also increase. This is because the agent should start rating actions that would cause it to fall off the map or burn to death to have high negative rewards. As a result, the agent should survive on the map longer and complete maps more consistently as it completes more episodes. This can be seen from the results of the training sessions in Figure 9 and Figure 10 below.

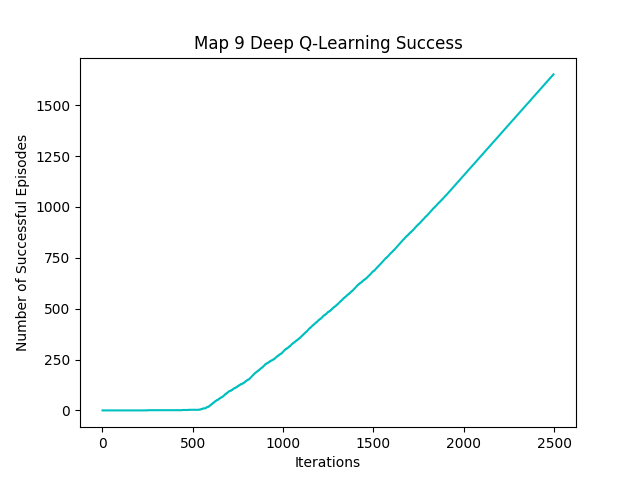

Figure 9: Map9 Success per Episode Graph

As can be seen from Figure 9, in the beginning, the graph shows a much slower increase indicating that it was dying before reaching the goal block in most of the early episodes. As the agent iterates through more episodes, the slope for the number of successful episode changes to a linear curve, meaning every episode is successful.

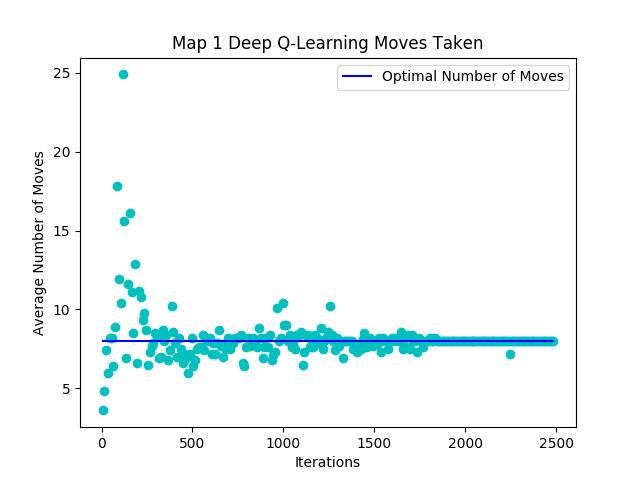

Figure 10: Map1 Success per Episode Graph

In Figure 10 shown above, you can see that the number of moves per episode is very small in the beginning due to the agent dying early on in the episode. The number of moves increases significantly in the middle as the agent starts learning to avoid lethal moves while also exploring the map to find the optimal path to the goal. You can see the variance in the number of moves reduces as the agent goes through more episodes. At the end of the training session, the number of moves per episode converges to a stable number indicating the agent has found the optimal shortest path.

Qualitative Measures:

The goal of our project is for an agent to learn the shortest path from a start block to a goal block while avoiding obstacles if necessary. To judge whether our agent accomplished this task, we used these three qualitative measures:

1. Whether path found is the optimal path (error rate metric)

2. Whether agent can complete map without dying

3. Amount of health upon reaching goal

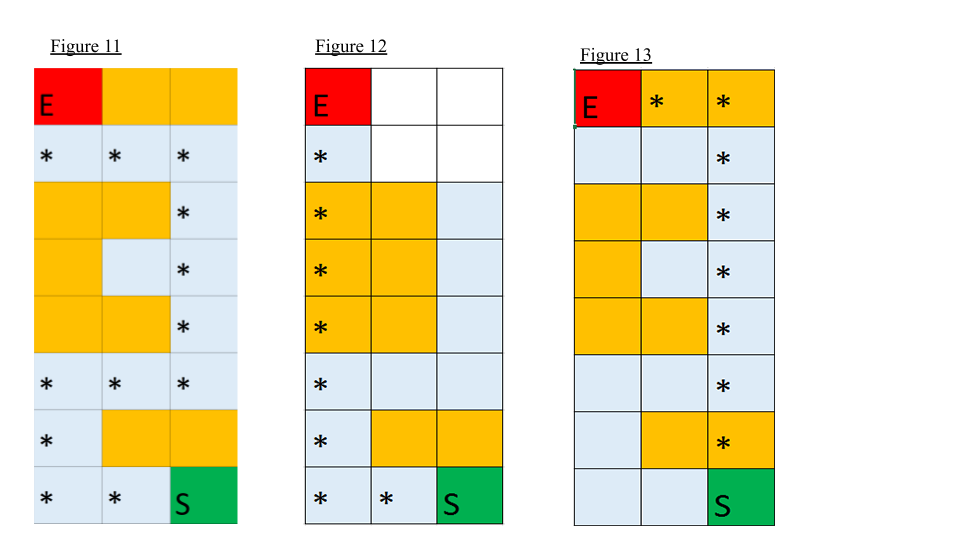

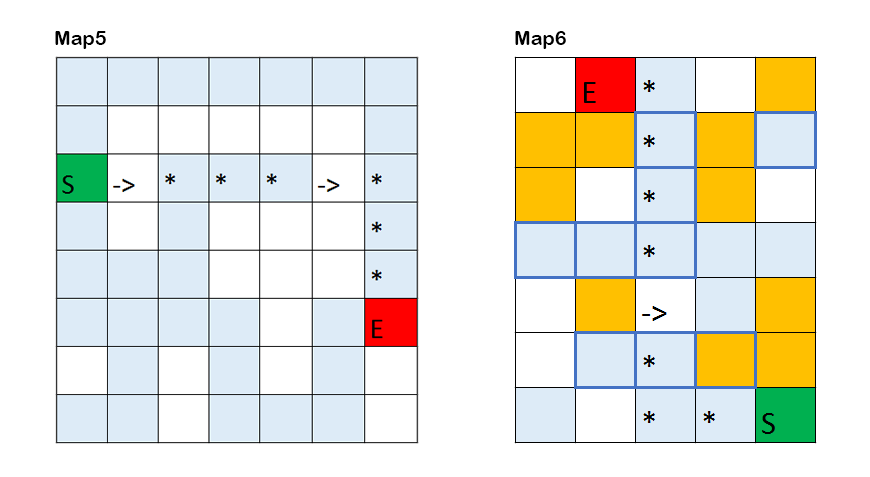

Our main qualitative measure is whether the path found is optimal. The optimal path is defined as a path to the goal that takes the least amount of moves while maximizing the agent’s remaining health. The agent can take damage along the path as long the damage taken would reduce the number of moves needed and does not kill the agent. To evaluate whether it can learn the optimal path, we created several test cases with a predetermined optimal path that we can compare to the path the agent learnt. The maps are specifically designed so that it will effectively test whether our agent can complete our qualitative measures. There are paths that result in no damage being taken but also takes slightly more moves (Figure 11), paths that kill the agent but result in less moves (Figure 12), and paths that would result in unnecessary damage being taken (Figure 13). There are also maps that require jumping over gaps (Figure 14) and maps that require platforming to find the optimal path (Figure 15).

Figure 14 & 15:

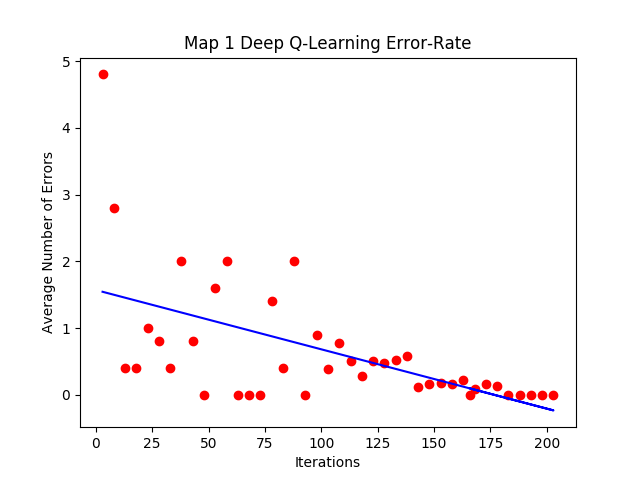

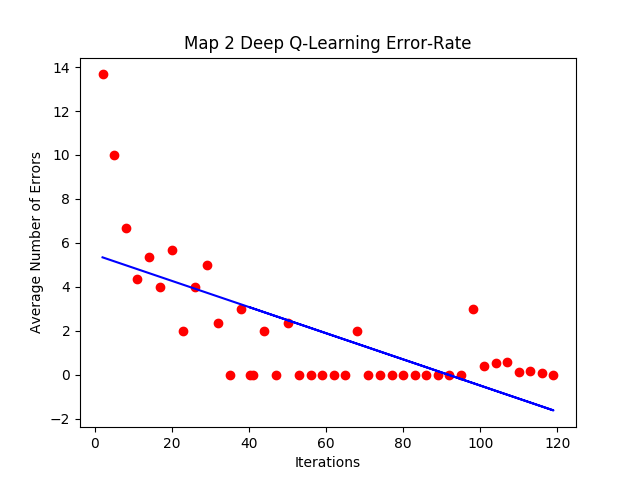

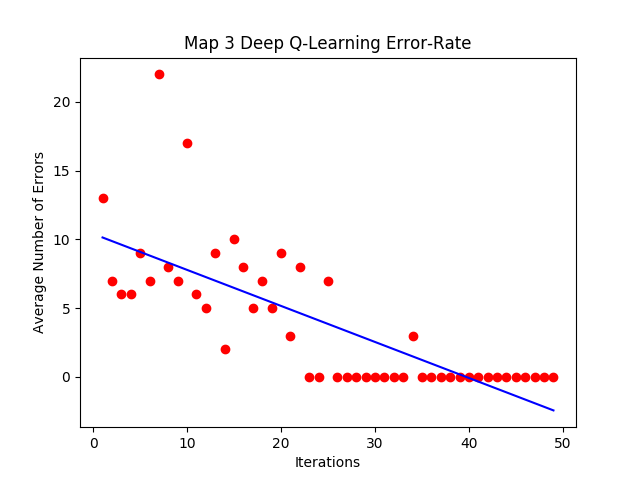

To evaluate the path the agent learns over a training session, we used the error rate metric. We define error rate of the path the agent chooses to be the number of moves that differ from the optimal path we designed for the map. If an agent dies before reaching the goal block, the error rate would reflect that by calculating the difference between the optimal number of steps and steps achieved. Figure 16, Figure 17, and Figure 18 below shows the graph of the agent’s error rate versus number of episodes for three different map.

Figure 16: Map 1 Error-Rate Graph

Figure 17: Map 2 Error-Rate Graph

Figure 18: Map 3 Error-Rate Graph

As we can see, all the maps have the same general trend. In the early episodes, the epsilon-greedy strategy for picking actions causes the agent to choose paths with high error rates as it randomly explores its options. As the number of episodes increases, the randomness factor decreases and the agent starts to prioritize paths with high reward values, which leads it closer to the optimal path. After several hundred episodes the error rate eventually converges to zero, meaning the agent has successfully found the intended optimal path. This shows that the agent has successfully completed the goal of our project.

References

- Q-Learning

- https://medium.freecodecamp.org/an-introduction-to-q-learning-reinforcement-learning-14ac0b4493cc

- Malmo tutorial6.py

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79pmNdyxEGo

- Figure 1: https://developer.ibm.com/articles/cc-reinforcement-learning-train-software-agent/

- Deep Q-learning:

- https://medium.com/emergent-future/simple-reinforcement-learning-with-tensorflow-part-0-q-learning-with-tables-and-neural-networks-d195264329d0